#networkanalysisFAIL

Malcolm Gladwell‘s recent piece for the New Yorker is getting a lot of play, ironically, on Twitter and Facebook. As much as I’d prefer not to be yet another (late) addition to what has already become a tired conversation over a short few days, the fact that I’m currently studying network theory and attempting to apply it to social movements means that this is one meme that this node can’t help but percolate.

While there is much that I agree with in the piece, and much that I don’t, what struck me most was his overly simplistic application of network analysis to a set of extremely diverse and complex situations. Granovetter‘s The Strength of Weak Ties (1973) introduced the theory that the transmission of innovation in networks occurs when bridges are made via weak ties between clusters of nodes (actors, people) that share strong ties. Among these strongly tied cliques, innovation is stifled by the very similarity of the group members, and it takes the input of information from other areas of a network, accessed through a weak tie bridge to facilitate the spread of innovation.

Gladwell’s hypothesis, as I read it, is that digital social networking tools such as Twitter and Facebook are comprised only of weak ties, and that what he terms as “high risk activism”, such as direct action in the face of violent, oppressive regimes, is performed by groups of actors with strong ties. Therefore, social networking sites cannot facilitate system-challenging activism. Furthermore, he argues that networks are heterarchies, and that only hierarchies produce effective political organisations.

There is no way that I can write a fully thought out and articulated response to Gladwell’s argument here, but here are a few points that serve as a starting place for why I think that his piece contains a kernel of truth (Twitter alone is not revolutionary) surrounded by poorly applied network theory and a limited understanding of social movements.

- It is an oversimplification to say that “The platforms of social media are built around weak ties”. Social networking sites, especially Facebook, have grown to such a scale that in some communities the social graphs that they represent are approaching representation of the offline, “real world” social graph. Users of these sites are developing complex modes of differentiating between their relationships with one another in ways that reflect and maintain the nuanced gradation of types and degrees of relations that make up their social networks both on- and offline.

- “High risk activism” by small groups with strong ties does not lead to social change without prior and post support by networks supported by weak ties. To only look at the “action” phase of social movement organising is to ignore the majority of work and forces that go into bringing about that action, and the follow-through on then using that action as a catalyst for change. It is true that when involved in high-stakes, potentially violent confrontations with organised institutions of power, it is preferable to do so in clusters that have a high degree of trust facilitated by strong ties, but it is wrong to suggest that the social relations of such clusters permeate the entire organising networks from which the tactical and strategic formulation of coordinated action arises. And after the action, it is not the strong ties of the group involved in the action that promote percolation of change through a broader social network, potentially leading to a cascade effect that precipitates a phase transition in the system as a whole, it is the dissemination of new possibilities from node to node, cluster to cluster, with significant leaps across distances in the network made possible by bridging weak ties.

- Gladwell seems to ignore the role of communications technologies in the civil rights movement. His account of the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins are told as if the growth of the protest (and counter-protest) over the days that followed the initial action, and the spread of similar protests throughout the South in the following weeks were all the result of face-to-face contacts. The role of various media – telephones, telegraph, newspapers, radio, and television is absent. Surely in a discussion of how contemporary media support or inhibit social activism the comparison with communications media of previous struggles is relevant.

As the language of network theory becomes popularised through the work of writers like Malcolm Gladwell, Chris Anderson, and Clay Shirky, we can expect to see discussions of all sorts of phenomena being discussed in the jargon of ties and flows, cliques and cascades. It will be important for people who have engaged deeply with these models and the social and technical subjects to which they are applied to keep their rampant misapplication in check.

Spaces of Refusal

Preliminary findings from new research into young Australians’ usage of mobile and social media reveals that while networks of information and communication technologies are changing rapidly, so too are the social practices that surround them. One interesting aspect of Kate Crawford‘s three year study into the practices and attitudes of 18-30 year olds across Australia is the comparison between mobile phone (and media) usage in urban and rural populations.

In cities, where 3G coverage is near-ubiquitous, the study captured a population that is, in a sense, always online. This ability to connect with others in one’s social network through a number of channels (face-to-face, telephone, text message, social networking sites…) can, in the situation of a failure in the technological networks, result in a “connectivity panic” in which the individual experiences anxiety as a result of being unable to use their device to connect to other people or sources of information. As a way of addressing this hyperconnectedness, nuanced social norms are emerging around how to deal with the ability to reach and be reached at all times. These may include taking intentional time offline, or away from social networking sites, but also in more subtle practices such as the differentiation of styles and modes of communication for various cliques and social clusters that one is part of. For instance, one might develop a norm for using telephone conversations as the primary mode of communicating with family members, but prefer the use of email for work contacts because of its ability to be answered in an asynchronous fashion, and thereby to seem less socially demanding on the person contacted.

In rural and regional locales, where data and telephony network coverage is far more patchy, attitudes and practices around the use of such technologies takes on a different character. In the situation where technological networks cannot be regularly or reliable accessed, social norms emerge that account for the fact that communication is not always possible. Respondents to the study reported practices such as writing and storing text messages while offline and transmitting large amounts in bursts when a signal became available. Conversely, in a low-coverage area it becomes more socially acceptable to not respond to a message at the time it was received by virtue of the fact that it is possible to have been out of range.

These methods for defining when and how one sends and receives information to one’s contacts can be seen as tactics by which individuals and groups are negotiating community norms in the context of rapidly changing technological and social network formations. In the case of placing limitations on one’s availability to the communication network, Crawford notes that these tactics can be seen as the creation of what Genevieve Bell has called “spaces of refusal”. However the creation of such spaces and times without connectivity to networked communications media should not be seen as a total rejection of the new communication technologies, but rather as an important aspect of negotiating new ways of being connected to online and offline communities.

Social Galaxies

A recent study from The Nielsen Company shows that US internet users are spending a greater proportion of their time online using social networking sites, in online games, and watching videos. Concurrent with this increase, a significant decrease has been seen in the proportion of time users are spending on email, instant messaging services, and “portals”, walled gardens often maintained by service providers (eg Yahoo, MSN). For the first time, US internet users are spending more time overall playing video games than they are using email.

To complicate questions around how users spend their time online, the function of online social networks and gamespaces has begun crossing over into the traditional territory of other categories of internet use as measured by Nielsen’s NetView studies. For example, instant messaging, email-like messaging, and accessing news and weather updates are activities that are increasingly taking place in social networking sites (as studied by Naomi Baron in Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World, 2008).

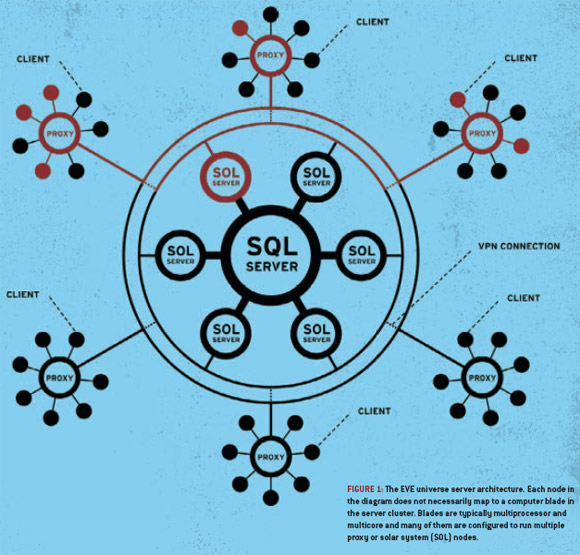

Furthermore, Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPG) increasingly exhibit characteristics of social networks, with the added complication that the personas that inhabit these spaces often straddle the identities of their “in-game” avatar and their IRL (In Real Life) or “meatspace” personage. A recent article by Kjartan Emilsson, Managing Director of CCP Asia, a game developer, highlights the interrelationship between the social networks that appear in gamespaces, the information architecture that underlies the game, and the physical computer networks on which they run. Emilsson’s description of these layers of networks (social, informational, and machinic) that make up the world of EVE Online, a MMORPG with 340,000 user accounts, centers around the benefits of employing a “single-shard database architecture” (ie everyone and everything in one big database) versus a “sharded architecture” (several seemingly continuous, but actually separate gamespaces). Emilsson argues that in spite of the significant technical difficulties posed by having such massive numbers of players coexisting in a single-shard architecture, the emergent social aspects of the game facilitated by maintaining a continuous gamespace create a richer game environment and by the very complexity of the system they create, encourage innovation by the game’s designers.

Although highly technical in its exposition, this article can be understood in conjunction with the work of theorists like Manuel Castells, Sherry Turkle, and Howard Rheingold when they discuss concepts of individual and community identities on the internet. Writing in the mid 1990s in reference to MUDs, the primitive predecessors of MMORPGs, Turkle notes “We come to see ourselves differently as we catch sight of our images in the mirror of the machine” (in Life on the Screen: Identity in the age of the Internet, 1995, p9). Technical choices made in structuring of networks that underlie the social spaces of MMORPGs play a significant role in setting the discursive frame for the construction of social identities in these worlds that exist both within and parallel to materiality.

If internet usage continues its drift away from modes like email and portals and towards social spaces such as social networking sites and massively multiplayer online games, how will the social practices of communication and identification online change? What will this mean for the technical infrastructure of the networks that support them?

leave a comment