Hey Hey it’s White Supremacy

(Dear Readers: apologies for the long absence. The fates have stepped in and made me a full-time carer for my injured partner and our baby, so little time for blogging. Background here. That said, some stories are too infuriating to ignore.)

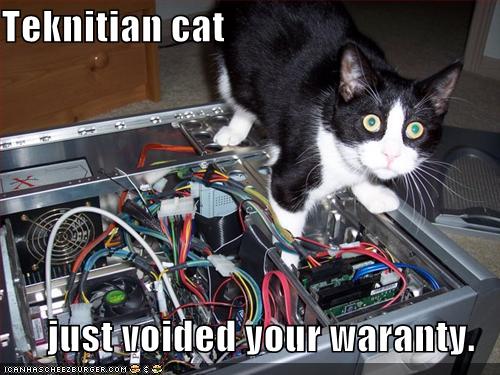

I’ve previously mentioned the prevalence of the Golliwog figure in Australia in these pages. Last week, on a reunion show of “Hey Hey It’s Saturday“, an extremely popular and long-running television variety show that ran all through my youth, an example of Australians’ obliviousness to the prevalence of racism in oz came roaring into the nation’s living rooms.

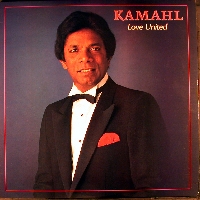

That’s right, producers and audience thought it was so funny the first time they did it 20 years ago, they brought it back for an encore. For those non-Australian readers, the cutaway to the caricature of a fat-lipped figure with the caption “Where’s Kamahl?” is a reference to a popular Australian lounge singer who is ethnically Tamil and was born in Malaysia.

Get it? Kamahl has dark skin! And sings! Hilarous, right? Kamahl is reportedly not amused.

Discourse around the story in the media and blogosphere is following a similar line to that begun in the exchange between Harry Connick Jr and Daryl Somers in the clip above. To summarise:

Rest of World: Hey Australia, that shit is racist and it’s mind-blowing that you’re still yucking it up to minstrel shows.

Australia: This is not America. Blackface is not considered racist here. Take a joke, mate.

Me: White Supremacy is so deeply entrenched in Australia that ridicule of people of colour, even in the crudest and most outmoded of forms of expression, is a socially acceptable form of entertainment.

Note that Daryl’s apology is directed to Harry for offending his American cultural norms, not for the content of the segment itself and its offense to people of colour.

While Australian blackface commonly mimics the Golliwog/Sambo/minstrel type, we also have an indigenous form. Growing up in North Queensland, King Billy Cokebottle was a popular performer who did his routine on a local radio program, when not out touring the pubs of the nation and selling audio cassettes by mail order.

It is important to remember that the assault on racial justice in Australia is not only taking place in the field of representation. The government has suspended the Racial Discrimination Act as part of the “Northern Territory Intervention” in order to enact policies that explictly discriminate against indigenous people, and deployed the and federal police to enact these laws. Lynchings occur, and semi-organized fascist groups are sprouting.

But it’s just a joke, mate…

Of Wogs and Golliwogs

There are certain things that it seems that Australia has not received the memo on. Glitches in the cultural continuum that send a jolt of culture shock through my system and let me know that I am in thoroughly americanized space, but not the US.

Being a new parent, I spend a fair amount of time browsing through childrens’ shops for cute new clothes or toys for Ramona. Many average mall baby/toy shops stock some version of the Golliwog.

As racist as the US is institutionally, this type of “Sambo” minstrel character is generally understood for what it is, a deeply insulting racist caricature from a bygone era. Apparently not here in the supposedly progressive Australia.

Until recently, Arnotts, an Australian company iconic for its Tim Tams, Iced VoVos, and many other baked confections sold biscuits called “Golliwogs”. (NOTE: I tried to find an image of this, but was amazed to find that I could not. Australians not so good with uploading? Arnotts on an aggressive revisionism campaign? weird…) In a seriously half-arsed PR move, “Golliwogs” became “Scalliwags” when Arnott’s sought to expand business in the US (maybe? not great sources on this).

Not only is the Golliwog still alive in Oz, it has spawned descendants. In Australia, dark-skinned people, particularly immigrants (often southern Europeans, Arabs), are often referred to as “Wogs”. “Wog” is a shortened form of “Golliwog”, first used by British troops to refer to Arabs, and later becoming a more general slur against people of colour. It is reported that in the 1960s soldiers from the Argyll and Southern Highlanders Regiment would display a Robertson’s Golly Badge for each Arab they had killed in Aden (Yemen), a British mandate until 1967.

Jason Di Russo remarks on the morphing context of the term “wog” over the past 20 years in his well thought out essay in The Australian. Russo does a good job of pulling the ridiculous framing of the Chk-Chk Boom non-story into focus. The story here is not whether or not Clare Werbeloff witnessed a shooting (she did not), it is the normality of white Australia’s caricatures of people of colour.

leave a comment